OUT NOW

ISSUE 43 FW23

KALEIDOSCOPE's Fall/Winter 2023 issue launches with a set of six covers. Featuring Sampha, Alex Katz, Harmony Korine, a report into the metamorphosis of denim, a photo reportage by Dexter Navy, and a limited-edition cover by Isa Genzken.

Also featured in this issue: London-based band Bar Italia (photography by Jessica Madavo and interview by Conor McTernan), the archives of Hysteric Glamour (photography by Lorenzo Dalbosco and interview by Akio Kunisawa), Japanese underground illustrator Yoshitaka Amano (words by Alex Shulan), Marseille-based artist Sara Sadik (photography by Nicolas Poillot and interview by Daria Miricola), a survey about Japan’s new hip-hop scene starring Tohji (photography by Taito Itateyama and words by Ashley Ogawa Clarke), Richard Prince’s new book “The Entertainers” (words by Brad Phillips), “New Art: London” (featuring Adam Farah-Saad, Lenard Giller, Charlie Osborne, R.I.P. Germain, and Olukemi Ljiadu photographed by Bolade Banjo and interviewed by Ben Broome).

FROM THE CURRENT ISSUE

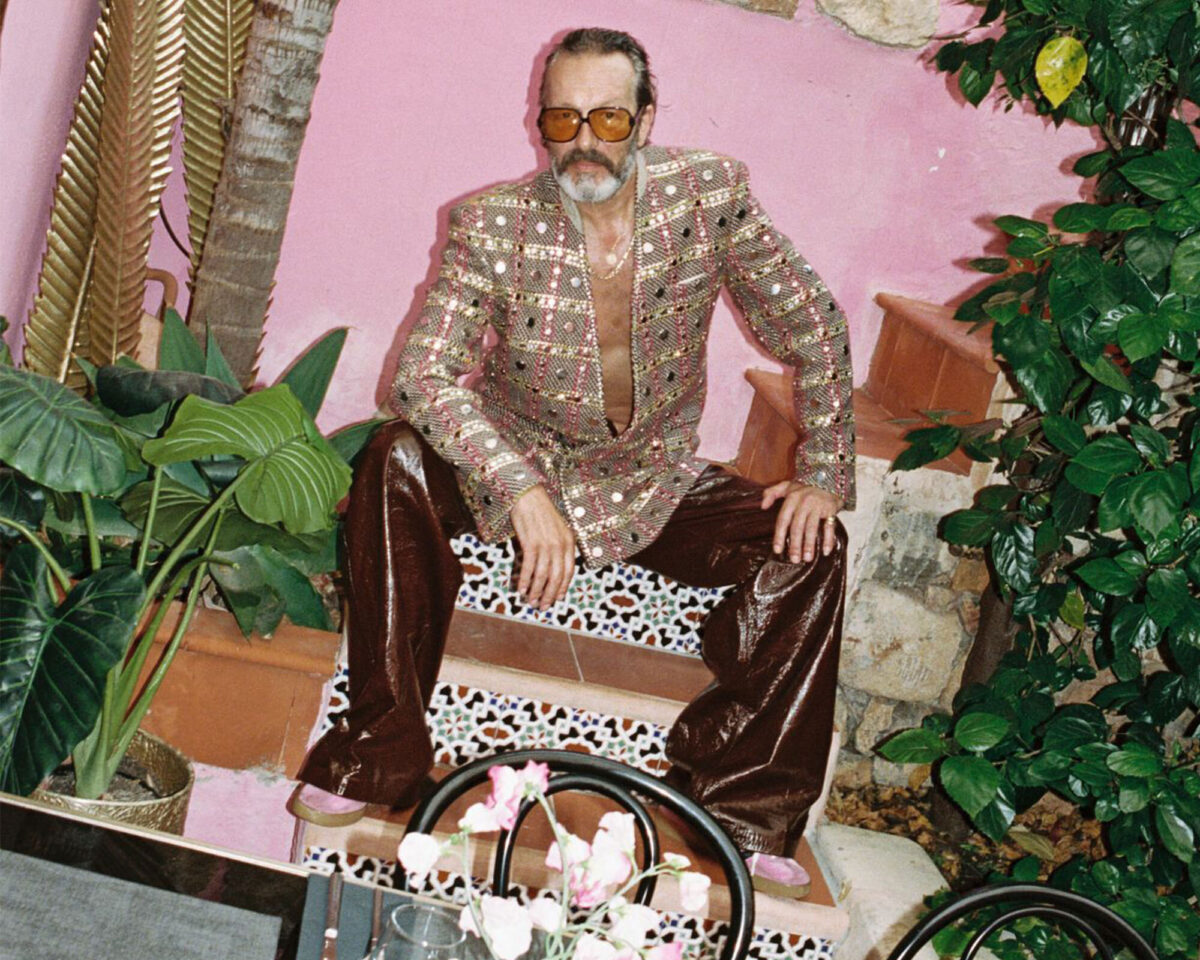

ESCAPE TO MIAMI

The most southernly city in the US, Miami exists in the tropical recesses of the American imagination: land of celebrity, thunderstorms, Tony Montana, and Art Deco architecture. Here, we meet the latest generation of Miamians—committed radicals in the fields of art, fashion, and music, who are dreaming up new narratives for the city they call home.

NEW ART: LONDON

The art world’s compulsion to categorize by the yardstick of “hot or not” has historically been the driving force behind the market and the gallery system. Commerce is intertwined with this metric, spurred on by the insatiable appetite to find talented young things to build up. This system is uninteresting: what’s in vogue rarely reflects those operating at the cutting edge. Who are those young emerging artists making work against all odds—work that is difficult and costly to make, store, exhibit, move, and sell? These five individuals typify this path. Working across video, sound, installation, and sculpture, they march onwards, carving out their own niche—exhibiting in empty shop spaces one day and major institutions the next. For them, making is guided by urgency, and persistence is motivated by blind faith.

SARA SADIK

KALEIDOSCOPE hosted a solo exhibition by Marseille-based artist Sara Sadik (b. 1994, Bordeaux), in November 2023 at Spazio Maiocchi in Milan, with the support of Slam Jam. Inspired by videogames, anime, science fiction, and French rap, Sara Sadik’s work explores the reality and fantasies of France’s Maghrebi youth, addressing issues of adolescence, masculinity, and social mythologies. Her work across video, performance, and installation often centers on male characters, using computer-generated scenarios to transform their condition of marginalization into something optimistic and poetic.

FROM THE SHOP

FROM THE ARCHIVE

MANIFESTO

In 2023, from June 22 to June 24 during Men’s Fashion Week in Paris, KALEIDOSCOPE and GOAT presented the new edition of our annual arts and culture festival, MANIFESTO. Against the unique setting of the French Communist Party building, a modern architectural landmark designed by legendary Brazilian architect Oscar Niemeyer, the festival will bring together visionary creators from different areas of culture across three days of art, fashion and sound. The 2024 edition will run from June 21 to June 23.

CAPSULE PLAZA

In April 2023, a year after the launch of the magazine, Capsule introduced Capsule Plaza, a new initiative that infuses new energy into Milan Design Week by redefining the design showcase format. A hybrid between a fair and a collective exhibition, Capsule Plaza brings together designers and companies from various creative fields, bridging industry and culture with a bold curation that spans interiors and architecture, beauty and technology, ecology and craft. The 2024 edition will run from April 15 to April 21.